What Happened in Vegas Didn’t Stay in Vegas

Three times a year, my friends Chris, Yev, and I pick a city. We show up. We do escape rooms.

Not just one. We do three, four, or more... and often back-to-back.

Our partners think we're strange. Taxi drivers think we're up to something illegal when we give them addresses in the sketchy parts of Vegas.

"Escape room," we say. "We lock ourselves in and solve puzzles."

Better to leave it there.

This time: Las Vegas. Coffee before the first room. Chris mentions his side project—an AI model predicting football games.

"I want to bet on it," he says. "But how much should I bet per game?"

"What do you mean?"

"My model gives me probabilities. Win percentages. I need a strategy."

"Payouts matter, right? Better odds mean bigger bets?"

"Exactly. And I can't bet everything on one game. One loss and I'm done."

We think about it.

"Two questions," Chris says. "How much per game? And how many games to spread across?"

We check the time. "We're late."

We never answered his questions. Not then.

Caught in the Vegas Trap

I don't remember how we did in that escape room. Probably fine. We're competitive.

But the betting problem stayed with me. Weeks. Months.

Then I found DJ's YouTube video about something called the Kelly Criterion.

The formula looked simple:

Where:

is how much to bet is the payout odds is your probability of winning is (i.e., )

Say you have a coin that lands heads

Kelly says bet

I stared at it.

What in the world...? How? Why? Who? When?

Two choices: accept the formula or take the red pill and enter its maze.

Only one real choice.

I read everything. How did an academic paper reach gamblers, investors, and hedge fund managers alike? DJ's video hinted at a few resources.

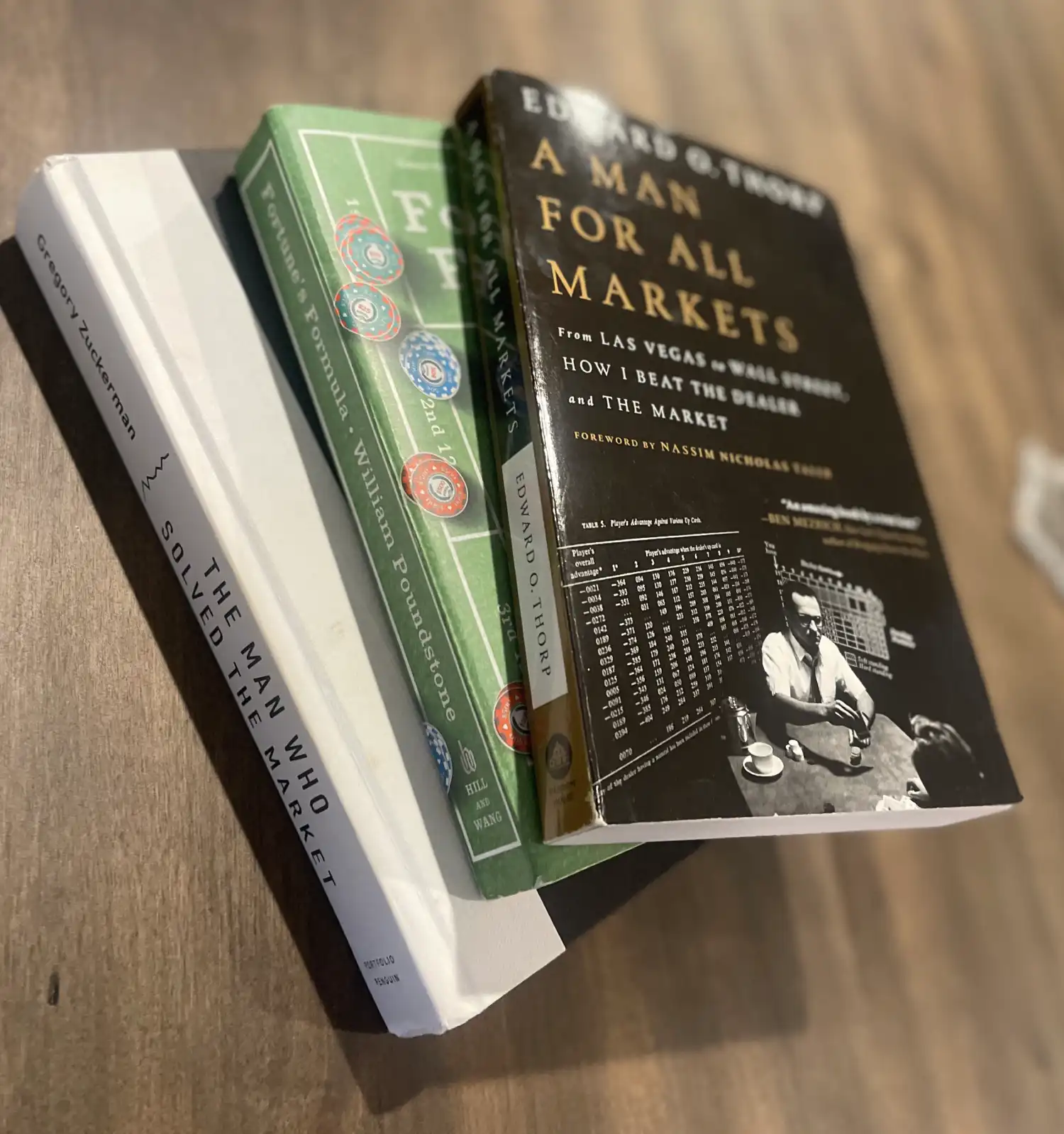

- Book: Fortune's Formula by William Poundstone

- Book: A Man for All Markets by Edward O. Thorp

- Book: The Man Who Solved the Market by Gregory Zuckerman

- Paper: A New Interpretation of Information Rate by John L. Kelly Jr.

- Paper: A Mathematical Theory of Communication by Claude E. Shannon

Months of confusion. Then discovery.[1]

Chasing the Intellectual Gamble

The Kelly Criterion isn’t just about betting; it’s about the power of compound growth.

"Compound interest is the eighth wonder of the world. He who understands it, earns it … he who doesn’t … pays it."

~Albert Einstein (maybe)

To grasp its full potential, I explored its history filled with some of the greatest minds in math and finance.

It's 1956. John L. Kelly Jr. works at Bell Labs. Claude Shannon’s information theory is revolutionizing communication. Kelly asks: what if we applied this to betting?

But what does it actually do?

Given the geometric growth as

, where is the initial capital and as the final capital after trades, the Kelly Criterion maximizes . In other words, the Kelly Criterion maximizes the expected logarithm of the geometric growth.

I repeated it. Different emphasis each time. "Maximizes... the expected... logarithm... of geometric growth."[2]

- What is geometric growth

? - Why maximize the expected

of ? - How do you derive Kelly from maximizing

?

Worst case? I'd learn something from brilliant people.

Note: The next section gets mathematical. I've broken it down step by step. If math isn't your thing, skip to Betting for Survival.

Cracking the Code

The Kelly Criterion is about balance. Don't risk too much. Don't risk too little. Find the sweet spot.

(1) What is geometric growth

Two types of averages matter: arithmetic and geometric.

Arithmetic mean vs geometric mean

Arithmetic mean is simple. Add everything. Divide by how many things.

Lionel Messi scores

Two goals per game. Almost as good as me in FIFA 99.

Geometric mean is different. It's for things that multiply:

Investment returns of

Average growth:

What about the arithmetic mean?

Arithmetic mean gives

That's interesting, though. Is the arithmetic mean always larger than the geometric mean?

Yup, the inequality holds always:

By why does the Kelly Criterion maximize the geometric growth?

Arithmetic growth vs geometric growth

Gain

Geometric mean tells the truth:

You're down. Not even. The geometric mean captures what actually happens when returns compound.

Bingo! Kelly maximizes geometric growth because that's what matters for long-term wealth.

(2) Why maximize the expected

To

Kelly says

Behold, the logarithm

Logarithms answer: "What power gives me this number?"

Binary?

The logarithm is the inverse of exponential growth. It simplifies multiplication:

Your wealth grows by

With logs:

Addition beats multiplication for calculation. Exponentiate to get back to real wealth:

But it's not just about easier math.

Greed is good—up to a certain point

Logarithms capture diminishing returns. The shape is concave. Each additional dollar matters less than the last.

Losses hurt more than equivalent gains help. Aggressive bets risk ruin. Logarithmic utility reflects reality.

Next time someone says "greed is good," tell them it depends on perspective. Then mention elawg—new slang for

You're welcome.

What happens to who don't

Without logarithmic utility, you chase expected returns. Big bets. High risk. Eventual ruin.

Scenario 1: No logarithmic utility

Start with

chance: double your money chance: lose half

Possible results:

- Win:

- Lose:

Expected wealth:

The arithmetic expected return suggests that, on average, you’ll end up with

Scenario 2: Using logarithmic utility (penalizing large losses)

Same scenario. Different lens.

Logarithms of outcomes:

- Win:

- Lose:

Expected log-utility:

Exponentiate:

Expected wealth:

The logarithm penalizes losses. Losing

Let's drive the point home with an extreme scenario: bet everything.

- Win:

- Lose:

Log-utility:

- Win:

- Lose:

Ruin is

Given a choice between finite returns and

(3) How is the Kelly Criterion derived from maximizing

The Kelly Criterion tells you how much to bet. Let's see how. Variables:

: fraction of wealth to bet : probability of winning : probability of losing : payout odds : initial wealth : wealth after the bet

If you win:

If you lose:

Expected wealth:

For long-term growth, use logarithmic utility. Factor out

This is the key equation. Find

Time for calculus. Differentiate with respect to

The derivative:

Solve for

There it is. The Kelly Criterion.

Simple. Powerful. Inevitable.

Curious how this relates to information theory? They both involve maximizing growth under uncertainty. [3]

Code has been cracked. Time to test it.

Betting for Survival

The room is cold. Metal table. Single coin in the center.

A timer: 60 minutes.

Then a voice. Mechanical. Familiar if you've seen the movies.

"You've gambled recklessly. Chased big wins. Relied on luck. Your choices brought you here. Let's see if you can gamble for survival."

A screen flickers. Coin flip game. We have

"Bet too much, one bad flip destroys you. Bet too little, you never leave."

Silence. The timer ticks.

59 minutes.

First few flips are careful. Every decision calculated.

Heads. Small win.

Tails. Small loss.

Something's wrong.

You grab the coin. Inspect it. The weight's off.

On the far wall, an inscription:

"All men die, but not all men truly live. Sometimes, a

The coin is biased.

You calculate:

"Bet

The strategy clicks. Flip. Heads. Up. Flip. Tails. Down.

50 minutes left.

Flip. Heads. Up. Flip. Tails. Down.

10 minutes left.

Every flip is agony.

1 minute remaining.

One last flip. Hands shaking.

Heads.

The door opens.

"You've escaped... for now."

We stumble out. The coin still in hand.

From Survival to Growth

Light blinds me as I step through the door.

Now I see the forms. The ideal bet. Plato would be proud.

Growth isn't about maximizing every win. It's geometric. Compounding. It extends beyond finance.

Chris's questions:

- How much per game?

- How many games?

Same question. Maximize

The Kelly Criterion is philosophy. It connects to antifragility—why Nassim Taleb wrote the foreword to Thorp's memoir.

The Ultimate Bet

Wealth grows geometrically. So do skills. Relationships. Mindsets.

These are the foundations.

The Kelly Criterion: avoid instant gratification. Prioritize compound growth.[4]

What will you bet on?

How will you ensure your decisions compound—not just today, but forever?

We'll keep betting on friendship. Compounding it over time.

The richest returns come from bonds, not numbers.

Footnotes

[1] Read Kelly's original paper and Poundstone's Fortune's Formula. ↵

[2] In economics and finance,

[3] Shannon's channel capacity formula:

[4] Key considerations: Full Kelly is volatile. Many use half or quarter Kelly. Estimating probabilities is hard—use Bayesian methods. The world isn't static—adapt your strategy. ↵